The Apple India Sanchar Saathi Preload Privacy Standoff intensifies as the tech giant rejects the mandate to pre-install the state-run cyber safety app on iPhones, citing security vulnerabilities and fundamental iOS privacy standards. The move sparks a major political row over digital surveillance.

Apple India Sanchar Saathi Preload Privacy Standoff

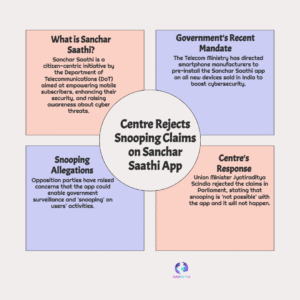

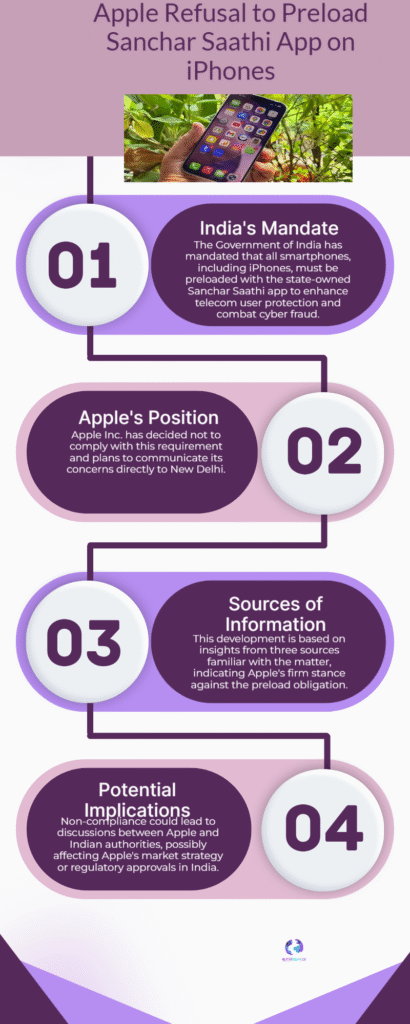

A significant and global tech standoff is brewing between the US-based tech giant, Apple, and the Indian government’s Department of Telecommunications (DoT) over a directive to mandatorily preload the state-run cyber safety application, Sanchar Saathi, on all new smartphones sold in the country. Reports confirm that Apple does not plan to comply with the order, citing fundamental concerns related to user privacy and security vulnerabilities within its proprietary iOS ecosystem. This resistance sets the stage for a critical confrontation, highlighting the ongoing global tension between state-mandated security and consumer digital rights.

The directive, issued by the DoT, mandates that manufacturers, including Apple, Samsung, and Xiaomi, must pre-install the Sanchar Saathi app on all new and existing devices via software updates within 90 days. The app’s stated purpose is to strengthen cybersecurity, help users block stolen devices using IMEI tracking, report fraudulent communications (spam/scams), and prevent the misuse of duplicate or spoofed devices in India’s massive second-hand mobile device market.

However, Apple’s firm stance, backed by its long-standing corporate policy of platform integrity and strict control over pre-installed software, signals its deep reluctance to compromise the core security architecture of its operating system. Industry sources familiar with Apple’s strategy indicate that the company views the mandatory pre-installation of any third-party or government-mandated app as a serious risk. Security analysts fear that for the app to function as a permanent system tool—as the initial order suggested by requiring functionalities not be restricted—it could necessitate system-level access, potentially creating a “permanent, non-consensual point of access” and severely weakening user protections against state surveillance.