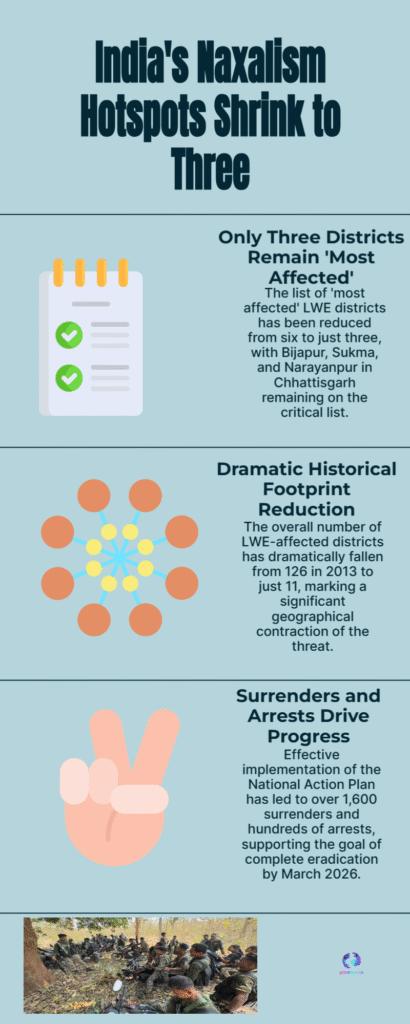

Government says Naxalism has shrunk to three “most-affected” districts — Bijapur, Sukma and Narayanpur — with LWE presence falling from 126 districts in 2013 to 18 now. Read a clear 600-word analysis of statistics, policy, security gains and remaining challenges.

The Union government on October 15, 2025 told Parliament that the Left Wing Extremism (LWE) threat has been significantly reduced, with only three districts — Bijapur, Sukma and Narayanpur in Chhattisgarh — now listed as the country’s “most-affected” zones. Officials said the overall number of LWE-affected districts has fallen from a peak of 126 in 2013 to just 18 today, a shift the government describes as evidence of sustained security operations and focused development work.

The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) released figures showing 312 LWE cadres killed, 836 arrested and 1,639 surrendered and reintegrated since the current government began its intensified counter-insurgency push. Among those listed as neutralised in operations were senior Maoist leaders, including members of the politburo, the statement said — underlining the leadership decapitation the government credits for weakening the movement’s operational reach.

Several districts that were previously classed as “most affected” have been removed from that category in the latest exercise. Gadchiroli in Maharashtra, West Singhbhum in Jharkhand and Kanker in Chhattisgarh were dropped from the most-affected list, reflecting a steady attrition in active militant influence in those areas. Authorities attribute the gains to a combination of precise, intelligence-led operations and people-centric interventions under the National Action Plan and Policy against Left Wing Extremism.

New Delhi’s target to eliminate Naxalism by March 31, 2026, is now being cited by officials as achievable, given the downward trend in hot spots. The government emphasised its multi-pronged strategy: security operations to contain and dismantle cadres; development projects to address local grievances and infrastructure deficits; and surrender-and-rehabilitation schemes that bring former cadres back into mainstream livelihoods. Authorities argue that the convergence of security and development has helped shrink the so-called “Red Corridor” once projected to stretch from Nepal to Andhra Pradesh.

Economically, the retreat of Naxal influence can open space for infrastructure, mining and agricultural investment in previously insecure areas — but success depends on responsive governance. If development projects fail to deliver visible benefits, or local disputes over land and resources are mismanaged, fresh grievances could feed a cycle of unrest. The next steps for authorities will therefore not only be tactical — completing counter-insurgency operations — but strategic: ensuring visible, equitable development in the most-affected districts and their peripheries.